William Henry Fox Talbot

William Henry Fox Talbot

René Talbot

by Lester Golden

It was love at first sight--the towering mast rising over the neo-classic J-class deck and hull of White Eagle in the 1992 Amsterdam Boat Show. I walked on board and asked a crew member to see the captain. Rene was the captain to whom I told the story of my less than year old company producing photography and brochures for yachtbuilders. He told me the compelling story of the world’s first post-communist superyacht built in Gdansk with a mixed German and Polish crew that worked together in English.

So began a 30 year long friendship with my most unique, passionate and obscenely generous client, one in which our brochures lived in his basement, I stayed in his downstairs office bedroom and ate his Polish partner’s marvelous cooking. Sehr lekker Schwabische Maultaschen at the bar down the street were also on this friendship’s menu.

It began with an unforgettable photo shoot in early October 1992 in Villefranche and in the Nioulargue classic yacht regatta in St. Tropez on love at first sight White Eagle. There were several points in common for a meeting of the minds. Rene was an Italophile who has a very loving relationship with food and my partner Jason and I lived in Milan. I found Rene’s French to be as funny as he found my klein schlechtes Gymnasium Deutsch; gute Auchsprach, aber Grammatiklos (Rene’s still waiting for me to put the verb in the right place). Rene was a self-taught intellectual autodidact who welcomed the challenge of talking to my trained historian’s mind, since he had some interesting family history to deal with.

I learned Rene’s family history in both German and English, directly from him and watching him talk to his Schwabische mutti, born in 1918. I also watched his post-yachting business activism develop out of this family history. We were less than a year apart in age and both children of the post-1968 era of activism, against the Vietnam War in the US, and against whitewashed amnesiac history in Germany. Rene’s particular family history exemplified the children’s generational reckoning with their parents’ and grandparents’ Nazi past.

Rene incarnated the civil war in the postwar German mind. His mother, who was born in 1918 and lived for a century, was from a village near Stuttgart. During the war she served as a nurse in the Polish epicenter of the Shoah, yet sincerely told Rene she had known nothing of the extermination camps. At a café on the Wannsee canal in Berlin, not far from the villa where the Nazis planned the Shoah, I have seen Rene bang the table and say to his mother, “how could you not know?”.*

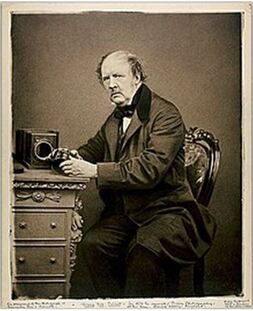

His father, conversely, was from the other Germany--a cosmopolitan French and English origin family that imported photographic equipment. Rene’s surname marks him as a distant descendant of the English scientist, photography pioneer and inventor William Henry Fox Talbot, the other side of the family:

Rene’s father’s view of the war was the polar opposite of his mother’s. In a room full of recruits in 1940 they asked who wanted to serve as a waiter in the officers’ club, and his hand shot up the fastest. So he stayed home in Berlin and learned everything about the Shoah from listening to conversations in the officers’ club. He told Rene he learned everything about the exterminations while they were happening, and while enjoying the company of officers’ wives while the officers were back at the front.

Rene’s story is one of confronting and choosing between these opposing narratives; reconciling intimate family connections with responsibility for collective history. Rene did so through activism:

Rene’s collaboration with Henry Friedlander and the Russell Tribunal helped expose how pre-Nazi coercive psychiatry was instrumental in turning what Prinzhorn called mental patients’ “pathological art” into “Entartete Kunst”—degenerate art. The story is worth a detailed narrative because it shows how psychiatrists abused the power the legal system gave them over the patients involuntarily put under their control to loot the art those patients created. Rene’s perseverance in disputing the psychiatrists’ continued control over these art works helped bring results: Germany’s law against involuntary commitment.

“The Prinzhorn Collection, which consists of more than 5,000 paintings, drawings, sculptures and textiles created mostly by schizophrenic patients between roughly 1890 and 1920, is scheduled to open to the public in a permanent installation next spring at the University of Heidelberg, home of the psychiatric clinic where the collection was originally formed. Last April, the university announced plans to present the collection in a renovated 19th-century lecture theater adjacent to the university’s neurological department. But a German advocacy group for the rights of the mentally ill is fighting to have the collection moved to Berlin, to be the centerpiece of a commemorative museum dedicated to the victims of Nazi euthanasia.

The bulk of the collection, largely amassed by psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn, has been an important inspiration for numerous European artists. It began as a group of some 127 artifacts assembled for an eventual “museum of pathological art” by Karl Wilmanns, head of the Psychiatric Clinic at the University of Heidelberg. When Prinzhorn came to the clinic as an assistant, he was put in charge of expanding that collection, and in 1919-20 acquired items from clinics across Europe, particularly in German-speaking countries, and as far afield as Japan and Peru. In 1922, a year after leaving the clinic, Prinzhorn published his still definitive Artistry of the Mentally III, which became required reading in avant-garde circles. Max Ernst took the book to Paris, where it became the bible of the Parisian Surrealists. The works caused a sensation in Germany and France during the ’20s, only to be forgotten after WWII and rediscovered in the ’60s.

Contributing to the current controversy is the use made of some of the Prinzhorn works by the Nazis. In 1937, four years after Prinzhorn’s death, Carl Schneider succeeded Wilmanns as director of the Heidelberg clinic and lent works for the Nazi’s “Degenerate Art” exhibition in order to help illustrate the Nazi thesis of the pathology of modern art. Furthermore, Schneider played an instrumental role in the Nazi euthanasia program, helping to send more than 20,000 mentally ill patients–including the authors of some of the works in the Prinzhorn collection–to the gas chambers.

This link between the University of Heidelberg and the Nazis is why Rene Talbot, spokesperson for a German advocacy group for the rights of the mentally ill, wants to have the Prinzhorn collection transferred to the Berlin museum. He claims that Prinzhorn “was the one responsible for implanting this notion of the existence of a pathological art. In this way he laid the foundation for the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition.” Talbot is counting on support from a number of Social Democrat politicians who are apparently sympathetic to his effort. (https://indexarticles.com/arts/art-in-america/ownership-dispute-over-prinzhorn-collection-art-work-by-the-mentally-ill-2/ )

Medicalizing repression made it easy to brand these artist/inmates as “useless eaters” unworthy of life to be killed by the T-4 euthanasia program. T-4’s social darwinist extermination of “useless eaters”—the disabled, mental patients, homosexuals-- was the startup template, genocide’s minimum viable product, for the mass extermination planned at the Wannsee conference. Without proof of concept from the Nazi doctors’ prototype, scaling up the machinery of genocide while at war would have been much harder.

Though I didn’t agree with Rene and Dr. Thomas Szasz about “the myth of mental illness”, Rene opened to me the window on how state-sponsored social and racial Darwinist policies were medicalized across multiple regimes:

So the untrained autodidact taught the professor. Another lesson autodidact Rene gave his prof friend late in life: “the right to laziness”. Rene was ahead of his time long, before COVID’s Great Resignation and the rise of quiet quitting. The paradox that this advocate of “the right to laziness” lived in was his Deutsche Grundlichkeit work ethic. Had he not been so ambitious, White Eagle would never have been built. His talent was that of a practicing, if not theoretical, anarchist who led and inspired a team without coercion. Rene’s talent’s rarity also proves anarchism can’t work, a question I’m sure Rene would be keen to debate when we next meet.

For that, and much more than guilt-free laziness, I’m thankful for Rene’s friendship.

---------------------------------

* Remark from me, Rene:

My mother´s ignorance about the true situation was even more tragic, as her very best girlfriend in the little town Öhringen where she grow up was Hansi Kahn, a Jewish girl living across the street. She had the luck to have parents with a Luxembourg passports and emigrating in time in the mid 30th to New York.

It remained a very good friendship also after the war, Hansi and my mother wrote each other. Hansi worked in the Iceland-air office and i meet her in NY 1987. A lovely lady and she took me out for a Japanese dinner and also booked flights for me :-)

I tried to revisit here in 1994 but did not meet here in her old address - so I lost track on her.

by Lester Golden

It was love at first sight--the towering mast rising over the neo-classic J-class deck and hull of White Eagle in the 1992 Amsterdam Boat Show. I walked on board and asked a crew member to see the captain. Rene was the captain to whom I told the story of my less than year old company producing photography and brochures for yachtbuilders. He told me the compelling story of the world’s first post-communist superyacht built in Gdansk with a mixed German and Polish crew that worked together in English.

So began a 30 year long friendship with my most unique, passionate and obscenely generous client, one in which our brochures lived in his basement, I stayed in his downstairs office bedroom and ate his Polish partner’s marvelous cooking. Sehr lekker Schwabische Maultaschen at the bar down the street were also on this friendship’s menu.

It began with an unforgettable photo shoot in early October 1992 in Villefranche and in the Nioulargue classic yacht regatta in St. Tropez on love at first sight White Eagle. There were several points in common for a meeting of the minds. Rene was an Italophile who has a very loving relationship with food and my partner Jason and I lived in Milan. I found Rene’s French to be as funny as he found my klein schlechtes Gymnasium Deutsch; gute Auchsprach, aber Grammatiklos (Rene’s still waiting for me to put the verb in the right place). Rene was a self-taught intellectual autodidact who welcomed the challenge of talking to my trained historian’s mind, since he had some interesting family history to deal with.

I learned Rene’s family history in both German and English, directly from him and watching him talk to his Schwabische mutti, born in 1918. I also watched his post-yachting business activism develop out of this family history. We were less than a year apart in age and both children of the post-1968 era of activism, against the Vietnam War in the US, and against whitewashed amnesiac history in Germany. Rene’s particular family history exemplified the children’s generational reckoning with their parents’ and grandparents’ Nazi past.

Rene incarnated the civil war in the postwar German mind. His mother, who was born in 1918 and lived for a century, was from a village near Stuttgart. During the war she served as a nurse in the Polish epicenter of the Shoah, yet sincerely told Rene she had known nothing of the extermination camps. At a café on the Wannsee canal in Berlin, not far from the villa where the Nazis planned the Shoah, I have seen Rene bang the table and say to his mother, “how could you not know?”.*

His father, conversely, was from the other Germany--a cosmopolitan French and English origin family that imported photographic equipment. Rene’s surname marks him as a distant descendant of the English scientist, photography pioneer and inventor William Henry Fox Talbot, the other side of the family:

Rene’s father’s view of the war was the polar opposite of his mother’s. In a room full of recruits in 1940 they asked who wanted to serve as a waiter in the officers’ club, and his hand shot up the fastest. So he stayed home in Berlin and learned everything about the Shoah from listening to conversations in the officers’ club. He told Rene he learned everything about the exterminations while they were happening, and while enjoying the company of officers’ wives while the officers were back at the front.

Rene’s story is one of confronting and choosing between these opposing narratives; reconciling intimate family connections with responsibility for collective history. Rene did so through activism:

- Against coercive psychiatry and lobbying to pass the German law that banned involuntary commitment (Irren Offensive).

- Organizing the Russell Tribunal that exposed the medicalization of the Nazis’ ideology of genocidal persecution (https://freedom-of-thought.de ). The Russell Tribunal provided additional documentary proof of survivor-historian Henry Friedlander’s thesis that the euthanasia program was the key to understanding the Nazi genocide; that “it was the doctors who needed the Nazis more than the Nazis needed the doctors.”

- Hosted my Auschwitz twin survivor friend, Otto Klein’s attendance as a witness at the Russell Tribunal’s trial of the Nazi doctors in 2001, at which Otto recounted Dr. Mengele’s experiments on him and other twins. “Il etait tres gentile” Otto said of Rene. I felt totally safe in sending my survivor friend to my big-hearted Berliner Freund.

- Trying to finance and build a museum to house the looted art in the Prinzhorn Collection and the art created by the victims of the Nazis’ euthanasia program, held hostage in the psychiatry department of the University of Heidelberg. The academic descendants of the perpetrators were still in possession of the art created by the euthanasia program’s victims, though they had no title to the art. With his own funds Rene got the Berlin Senate to give permission to build the museum in the Tiergartenstrasse 4 where the euthanasia program had been headquartered. But it could never be built since the Heidelberg psychiatrists who held the art wouldn’t allow it to be housed in a museum that would advertise their profession in exactly the way they preferred not to see.

Rene’s collaboration with Henry Friedlander and the Russell Tribunal helped expose how pre-Nazi coercive psychiatry was instrumental in turning what Prinzhorn called mental patients’ “pathological art” into “Entartete Kunst”—degenerate art. The story is worth a detailed narrative because it shows how psychiatrists abused the power the legal system gave them over the patients involuntarily put under their control to loot the art those patients created. Rene’s perseverance in disputing the psychiatrists’ continued control over these art works helped bring results: Germany’s law against involuntary commitment.

“The Prinzhorn Collection, which consists of more than 5,000 paintings, drawings, sculptures and textiles created mostly by schizophrenic patients between roughly 1890 and 1920, is scheduled to open to the public in a permanent installation next spring at the University of Heidelberg, home of the psychiatric clinic where the collection was originally formed. Last April, the university announced plans to present the collection in a renovated 19th-century lecture theater adjacent to the university’s neurological department. But a German advocacy group for the rights of the mentally ill is fighting to have the collection moved to Berlin, to be the centerpiece of a commemorative museum dedicated to the victims of Nazi euthanasia.

The bulk of the collection, largely amassed by psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn, has been an important inspiration for numerous European artists. It began as a group of some 127 artifacts assembled for an eventual “museum of pathological art” by Karl Wilmanns, head of the Psychiatric Clinic at the University of Heidelberg. When Prinzhorn came to the clinic as an assistant, he was put in charge of expanding that collection, and in 1919-20 acquired items from clinics across Europe, particularly in German-speaking countries, and as far afield as Japan and Peru. In 1922, a year after leaving the clinic, Prinzhorn published his still definitive Artistry of the Mentally III, which became required reading in avant-garde circles. Max Ernst took the book to Paris, where it became the bible of the Parisian Surrealists. The works caused a sensation in Germany and France during the ’20s, only to be forgotten after WWII and rediscovered in the ’60s.

Contributing to the current controversy is the use made of some of the Prinzhorn works by the Nazis. In 1937, four years after Prinzhorn’s death, Carl Schneider succeeded Wilmanns as director of the Heidelberg clinic and lent works for the Nazi’s “Degenerate Art” exhibition in order to help illustrate the Nazi thesis of the pathology of modern art. Furthermore, Schneider played an instrumental role in the Nazi euthanasia program, helping to send more than 20,000 mentally ill patients–including the authors of some of the works in the Prinzhorn collection–to the gas chambers.

This link between the University of Heidelberg and the Nazis is why Rene Talbot, spokesperson for a German advocacy group for the rights of the mentally ill, wants to have the Prinzhorn collection transferred to the Berlin museum. He claims that Prinzhorn “was the one responsible for implanting this notion of the existence of a pathological art. In this way he laid the foundation for the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition.” Talbot is counting on support from a number of Social Democrat politicians who are apparently sympathetic to his effort. (https://indexarticles.com/arts/art-in-america/ownership-dispute-over-prinzhorn-collection-art-work-by-the-mentally-ill-2/ )

Medicalizing repression made it easy to brand these artist/inmates as “useless eaters” unworthy of life to be killed by the T-4 euthanasia program. T-4’s social darwinist extermination of “useless eaters”—the disabled, mental patients, homosexuals-- was the startup template, genocide’s minimum viable product, for the mass extermination planned at the Wannsee conference. Without proof of concept from the Nazi doctors’ prototype, scaling up the machinery of genocide while at war would have been much harder.

Though I didn’t agree with Rene and Dr. Thomas Szasz about “the myth of mental illness”, Rene opened to me the window on how state-sponsored social and racial Darwinist policies were medicalized across multiple regimes:

- The Americans’ Tuskegee experiments.

- Eugenics-driven forced sterilizations and/or forced removal of children from their families in Sweden, the US, Canada, Australia and Israel (of Sephardic Jewish children).

- And the Soviets’ psychiatric abuses.

So the untrained autodidact taught the professor. Another lesson autodidact Rene gave his prof friend late in life: “the right to laziness”. Rene was ahead of his time long, before COVID’s Great Resignation and the rise of quiet quitting. The paradox that this advocate of “the right to laziness” lived in was his Deutsche Grundlichkeit work ethic. Had he not been so ambitious, White Eagle would never have been built. His talent was that of a practicing, if not theoretical, anarchist who led and inspired a team without coercion. Rene’s talent’s rarity also proves anarchism can’t work, a question I’m sure Rene would be keen to debate when we next meet.

For that, and much more than guilt-free laziness, I’m thankful for Rene’s friendship.

---------------------------------

* Remark from me, Rene:

My mother´s ignorance about the true situation was even more tragic, as her very best girlfriend in the little town Öhringen where she grow up was Hansi Kahn, a Jewish girl living across the street. She had the luck to have parents with a Luxembourg passports and emigrating in time in the mid 30th to New York.

It remained a very good friendship also after the war, Hansi and my mother wrote each other. Hansi worked in the Iceland-air office and i meet her in NY 1987. A lovely lady and she took me out for a Japanese dinner and also booked flights for me :-)

I tried to revisit here in 1994 but did not meet here in her old address - so I lost track on her.